Dr Ronita Mahilall professional training is in the Social Sciences: Social Work. She has a Masters in Social Science from UNISA and a PhD in Psychology from Stellenbosch University. She was offered a 2-year post-doc fellowship at National Institute of Health (NIH), in Washington DC but had to cut that program short to come back to South Africa as her mom was diagnosed with a terminal illness.

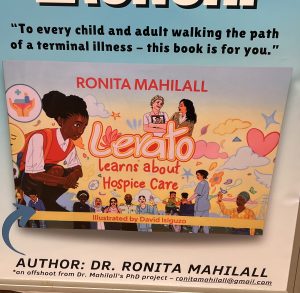

She is the Chief Executive Officer of St Luke’s Combined Hospices, Cape Town, SA. She works as an associate researcher at Stellenbosch University and a guest lecturer at the University of Minnesota, in the US as well as with universities in Sweden and Austria. She also supervises students at South African College of Applied Psychology (SACAP) and Management College of Southern Africa (MANCOSA), Cape Town. This book publication “Lerato Learns about Hospice” also adds another accolade to her esteemed professional achievements.

Who is Ronita Mahilall, both personally and professionally?

I am a mother (my greatest achievement yet!), a wife, a daughter and a sister. I genuinely love helping people and I have a passionate relationship with food! Professionally, I am a social worker and the trajectory of my career changed to a sharp focus on disability when we were blessed with our first child, Perez, who was born with Down syndrome. I subsequently headed the Social Services Department of the KwaZulu-Natal Blind and Deaf Society and thereafter led one of the largest non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in KZN, working with orphaned and vulnerable children, who were left destitute as a result of the AIDS pandemic. I am currently the chief executive officer (CEO) of St. Luke’s Combined Hospices (SLCH). I successfully completed my PhD at Stellenbosch University, through publication, and am currently a research associate at the University. I am also working with universities in the USA, Europe and locally as well as supervising master’s/PhD students.

Tell us briefly about your academic journey to your PhD dissertation and how it influenced you to write this book.

As the CEO of St. Luke’s, I was positively overwhelmed by the quality and scope of the palliative care services provided. However, the spiritual care component was significantly underrepresented in the palliative care package. By bringing academic recognition to spiritual care, the aim was to give it its rightful place within the palliative care services bouquet. During the course of engaging with the participants (nationally, provincially and at St. Luke’s), I was struck by the conscious lack of engagement with children when delivering bad news; for instance, a terminal diagnosis. Children, as we know, are curious and when left out of important family gatherings and conversations, they tend to create their own narratives. This book is an opportunity to allow for the facilitation of difficult conversations with children by the patient/caregiver/professional therapist etc.

What are the prevailing social and cultural dynamics or taboos that make palliative care still shrouded in mystery?

South Africa is one of the most diverse countries in the world, that notwithstanding, South Africans also display significant tolerance and sensitivity towards cultural diversity. Note in point is that SA is one of the few countries that proudly boasts 12 official languages and celebrates key religious holidays as public holidays. This being said, fear of death and dying seems to be a basic human fear. Some cultures, typically African, worship their ancestors, suggesting that death and dying have less mystery attached. Yet other cultures and religions find it daunting to talk about death and dying. It is, therefore, the responsibility of healthcare providers (medical and psychosocial) to approach this topic within the context of holistic care.

What is your opinion on palliative care and the right to death with dignity?

My opinion is that palliative care is a fundamental right. It is unfortunate that our SA government only recognised palliative care as part of the continuum of health care as late as 2017. Institutions such as St Luke’s that have worked in the palliative care space for the past 45 years, have always valued palliative care intervention that is underpinned by compassion and death with dignity.

What are the best approaches and practices that we as adults can adopt in addressing talking about palliative care with children?

Honesty! It is our responsibility as parents, grandparents, caregivers and professionals to have conversations about death and dying and to make it part of our children’s vocabulary and common conversations. It is also critical for educators at school to be equipped with the knowledge and skills to have those conversations in those formative years. This is another reason why I wrote this book – the intention was for it not only to be used as a tool in health care settings but to be used as conversation openers for educators. If adults are comfortable with death and dying and normalise it, then children, who largely model their behaviour on adults, would grow up without prejudices and fears of death/dying and palliative care.

As the writer, what would you want to achieve with this book?

Primarily to create an awareness on hospice and palliative care and to normalise it as well. I have deliberately left the last few pages blank so that the family reading the book could write their own story and have the book as a keepsake or to be handed down to the loved ones left behind after the person receiving palliative care has passed on.

Tell us more about the African Palliative Care (APCA) conference in September, where you will be presenting your dissertation/study.

It is my view that conferences, especially where third world countries are key role players, give participants coming from those countries an opportunity to share lived experiences that often are not typical of developing countries. This makes for very engaging learning and sharing. The tracks in this conference speak to innovative ways in which paediatric palliative care and palliative care in general are showcased. I submitted the abstract largely on a whim, and I was confident that, given the diverse tracks of the conference, it stood a chance of being accepted on either of the tracks. It is my aim for the book, through my presentation at the conference, to shine a light on palliative care and, in particular, to normalise conversations with children affected by patients receiving palliative care. That is why the book has a reader’s guide included. The book was written as a conversation between prepubescent children set in a township in Cape Town, SA. One child (Tinus), whose brother was being cared for by a hospice and passed on and another child (Lerato), whose mother was currently receiving palliative care from hospice staff, are having a conversation. Tinus becomes the support for Lerato and answers her questions (that a child would have). These answers give her comfort, hope and knowledge, and significantly reduce her fear.

Where can one get the book and what is the retail price?

Currently, it is sold as a hard copy at R150,00 per copy. It is my intellectual property, but a percentage of all sales will be donated to St Luke’s in support of the palliative care work being done. I intend to get it onto Google Books (e-books) as well, but I am not there yet.

What advice would you give to younger professionals entering the palliative care profession today?

My advice to young professionals, especially in the medical fraternity who are training to save lives and cure illnesses, is that a terminal diagnosis is not a ‘failure’ on their part. Referring a patient for palliative care early on is actually doing the patient a huge service as they can then access psychosocial interventions too, such as spiritual care, counselling etc. Furthermore, advice to young professionals in the psychosocial spaces are to consider bereavement counselling at the point of diagnosis as bereavement is not only grief as a result of death but is also the grieving one’s inability to be a breadwinner, their inability to master the simple skills of daily living, their inability to be a fully functioning parent/grandparent/spouse, to drive etc. I believe strongly that while there may be a limit to cure, there is no limit to care. Young professionals should embrace that too.

Read more about her Abstract:

https://arts.sun.ac.za/files/2025/08/Thesis-Abstract-Ronita-Mahilall.pdf